|

The

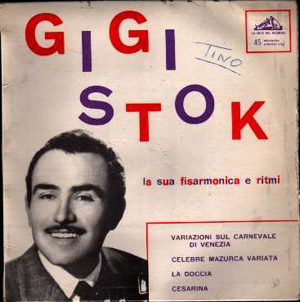

City of Parma is mourning the loss of one of its musical sons. Gigi

Stok died at the end of February this year after a 3- year battle against

Alzheimers. He was buried on the 2nd of March in the village of his

birth, Bianconese in the province of Parma where he began his career

accompanying his father. The

City of Parma is mourning the loss of one of its musical sons. Gigi

Stok died at the end of February this year after a 3- year battle against

Alzheimers. He was buried on the 2nd of March in the village of his

birth, Bianconese in the province of Parma where he began his career

accompanying his father.

Gigi Stok was born Luigi Stocchi in 1920. He studied the accordion under

the guidance of Maestro Marmiroli, who together with Savi were amongst

the best accordionists of their era. At the age of 13 he made his public

debut together with his father, a singing storyteller, and here started

his road to fame. After the interruption of the second World War, Stok

joined the Tamani Orchestra a famous ensemble of its day, and began

to include some of his own compositions in the orchestra's repertoire.

He, along with a handful of accordionists of his generation, were the

players that introduced the element of virtuosity into dance music.

Harry James on Trumpet and Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman on Clarinet

did a similar thing with the American Swing bands of the 1940s. At the

end of the 1940's, after an audition where he played one of his own

compositions namely Elettrico, His Masters Voice/EMI in Milan, realising

his virtuosity offered him a recording contract, a relationship which

was to last until the 1970's.

I first met him in 1982 in a village in the mountains called Cassio

where he spent his summers and annually organised a local accordion

festival. He had already retired from playing live by then but offered

me, then aged only sixteen, words of encouragement in my work with my

then fledgling band. I spoke to him only a few years ago on the telephone

and he recounted many interesting stories about his career. During this

conversation I realised that his legendary reputation for technical

excellence was not a myth. He told me that he was never really happy

with those early recordings for His Master's Voice because more often

than not he only got to do one take and if he'd made a slight slip the

producer would argue that it didn't matter because the energy was right.

Being young and new to the game he didn't want to argue so many years

later in the 1970s and 80s he re-recorded many of those early tracks

to a standard that was to his satisfaction. I have to say that anyone,!

no matter how musical, would be hard pressed to find the slip-ups that

bothered him so much in those early recordings. Although his later recordings

are beautifully played and technically perfect I have to say that those

early recordings do have that certain energy that the producer liked

so much.

They are usually played by Stok, accompanied by an acoustic guitarist

and a Double Bassist joined by a pianist for the Tangos. The recordings

breathe, like a live recording of a trio or a quartet should and so

are more interesting musically than the later so-called "technically

perfect" recordings which usually involve electric guitar, electric

bass and sometimes keyboard and sax and are probably multi-tracked.

His successful recording career still required him to promote himself

by a tiring touring schedule. It was during this time that he took on

a black singer of Cuban origin by the name of Marino Barreto, hitherto

unheard of in 1950s Parma, where he would have found it difficult to

find a hotel that would give him bed and board. Nevertheless prejudices

were soon defeated by this singer's wonderful voice. After a brief success

with Stok's band, Barreto took off on an even more successful solo career

taking half of Stok' s band with him. Within a fortnight the not-to-be-defeated

Stok had formed another band with which he had continued success.

In 1966 he was asked to compose a piece for a Film that was to star

the actor Ugo Tognazzi, well-known in Italy if not so much abroad. The

film was L'Immorale and the piece was Vecchi Ricordi. Although ballroom

dancing went out of fashion in the 1960's, Gigi Stok did not, and remained

popular especially amongst Italians from his region living outside Italy.

In the brief period when the accordion would get booed off the stage

he played bass in the band and started arranging light classical music

for the accordion ready for it's anticipated comeback. Some of these

worked well and others less so.

His

Paganini's Moto Perpetuo is impressive although for someone whose left-hand

technique was so good, his decision to record it with electric bass

and guitar is perplexing. Triumphal March from Aida (Verdi), Va Pensiero

from Nabucco (Verdi), Radetzky March (J.Strauss) La Campanella (Paganini)

amongst others were recorded in the same way. One can only imagine that

a certain amount of folklorisation was required in order to cater for

his audiences who probably would have known the accordion only as a

vehicle for dance music or folk and perhaps were not yet ready for pur!

ist approach of his contemporary Marcosignori. His

Paganini's Moto Perpetuo is impressive although for someone whose left-hand

technique was so good, his decision to record it with electric bass

and guitar is perplexing. Triumphal March from Aida (Verdi), Va Pensiero

from Nabucco (Verdi), Radetzky March (J.Strauss) La Campanella (Paganini)

amongst others were recorded in the same way. One can only imagine that

a certain amount of folklorisation was required in order to cater for

his audiences who probably would have known the accordion only as a

vehicle for dance music or folk and perhaps were not yet ready for pur!

ist approach of his contemporary Marcosignori.

By the late seventies Gigi Stok decided to take things a little easier

and launched a band called I Cadetti di Gigi Stok where he would make

the odd guest appearance but the accordion playing was left largely

to Corrado Medioli. In respect of his technical perfection and contribution

to Italian accordion music of the popular and ballroom genre, he was

awarded the Life Achievement Award at the London Accordion Festival

2001. He was unfortunately unable to attend due to his already advancing

illness but Corrado Medioli, who brought a letter of thanks from his

wife Carolina, accepted the award on his behalf.

I was very pleased to be able to arrange a special medley of is hits

for performance with the BBC Concert Orchestra at the same festival

and together with Mauro Carra and Corrado Medioli had great fun playing

it to an enthusiastic auditorium. It consisted of some of his more famous

international successes, along with one or two of his lesser-known works.

Vecchi Ricordi, Elettrico, Tango Gagliardo, L' Indiavolata, L'Italiano

a Parigi, Signora Fisarmonica, Il Silenzio Fuori Ordinanza and Brioso.

The accordion

has moved on considerably in the last fifty years. Accordionists are

playing music never before imagined so it is easy to scoff today at

musicians that were pioneers in their day because their field was perhaps

one that has always been associated with the accordion. The "Accordion

Virtuoso", who plays Monti's Czardas and Dizzy fingers may have

become a clichè today but play these pieces on a pre-war instrument

and he can be likened to some of the young eastern- european players

seen heroically competing in festivals all over Europe today on accordions

held together with gaffer tape. Add to this the amount of music that

the average European of that era was exposed to, owning a radio if lucky,

not to mention a TV and a different picture emerges.

Gigi Stok and his peers made young players of his generation and later

my own generation aspire to playing pieces where a good technique rendered

a piece exciting and a sign of bravura. His left-hand semi-quaver run!

s in fast waltz tempo made many players realise that the left-hand keyboard

was for more than just vamping along. Gigi Stok limited himself to playing

the dance music he knew best but raised the profile of the accordion

and it's technical possibilities within that genre. I fully acknowledge

and appreciate the influence his music had on me as an enthusiastic

teenager wishing to attain the clarity and crispness of this man's dazzling

technique. He will be missed by many but I for one shall always keep

a handful of his pieces well practised and regularly performed for a

willing audience.

Romano Viazzani

|