|

|

|

The

names Palmer and Hughes are inseparable in the minds of accordionists

the world over. Indeed, some do not even realize that these are the names

of two men not one. The

names Palmer and Hughes are inseparable in the minds of accordionists

the world over. Indeed, some do not even realize that these are the names

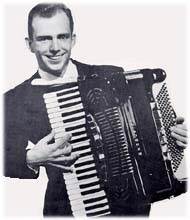

of two men not one.A few months ago, Bill Hughes succumbed to cancer. He was only 52 years old. His was a lifetime of accordion achievements. Innovative, talented, personable, he left an indelible print on accordionists everywhere. It was he and Palmer who perfected and extended the perimeters of concert accordion work well beyond the limits of their day. No one could better write this article tracing Bill Hughes' lifeline as it ran its parallel course with accordion history, than Bill Palmer - his colleague, partner, and friend of 40 years. Here is a rare opportunity to share some intimate reflections of the dreams, untiring efforts and accomplishments which made these two men a single entity - that phenomenon known as Palmer-Hughes.  It

will be impossible to adequately summarize all of the contributions Bill

Hughes made to the accordion community and his great influence on a host

of friends, fans, and admirers. He was a splendid and busy teacher, a

lecturer and educator, a conductor, a writer, composer and arranger, an

excellent jazz musician and a concert performer. His contribution in each

of these fields were nothing less than phenomenal. It

will be impossible to adequately summarize all of the contributions Bill

Hughes made to the accordion community and his great influence on a host

of friends, fans, and admirers. He was a splendid and busy teacher, a

lecturer and educator, a conductor, a writer, composer and arranger, an

excellent jazz musician and a concert performer. His contribution in each

of these fields were nothing less than phenomenal.My association with Bill Hughes began in Jackson, Mississippi in 1938, when he became my student at the age of 12. He was one of those rarely gifted students we call a natural musician. With no previous musical training he was playing professionally in less that six months after his first lesson. After just one month of study he was featured on radio station WJDX in Jackson, playing 15 minutes of accordion solos. They were not simply student pieces, but works like the overture to The Barber of Seville, and popular pieces like Night and Day. At the age of 14, Bill hosted a weekly amateur contest and show at one of the Jackson theatres, filling in with accordion solos. In 1940 he performed with Anthony Galla-Rini's Octette at the NAMM convention in New York City. On that same program, he performed Galla-Rini's arrangement of the overture from Il Guarany by Gomes. Bill studied intermittently with Galla-Rini, whenever he had the opportunity. From this association, Bill received much encouragement and inspiration. During the years of World War II, Bill was in the U.S. Navy band and had the opportunity to further his musical education at the U.S. Navy School of Music. He saw dangerous combat action in the South Pacific, and often related some of the close calls he had at the battle of Okinawa. In 1946, Bill and I enrolled as music students at the University of Houston, Texas. Since I was doing graduate work there, I urged the university to include the accordion in its curriculum. The chairman of the music department, Bruce Spencer King, challenged me to find an accordionist who desired this training and who could meet the rigid entrance requirements. That student would have to be able to cope with music literature of the same level as required of other keyboard majors. It is much to Bill Hughes' credit that he conceived of the idea of enrolling as my student on a test basis. Of course, Bill predictably amazed everyone with his technique and musicianship, and in 1946, the accordion was fully accredited by the University of Houston as an applied major. Accordionists were permitted to earn a bachelor's degree of music, or a bachelor's degree of arts, and even a master's degree, with accordion as their major instrument. The accordion was being accepted for elective credit at some institutions prior to that date, but I believe that this may have been the first time that a college or universty in the U.S. had ever accepted the accordion on an absolutely equal footing with piano, violin, organ, or any other instrument. Among our first enrollees was Lynlee Barry (now Allee), who became an ATG champion and was a U.S. representative at the Coupe Mondiale. Also enrolled was Pauline Oliveros, now regarded as one of the world's outstanding avant-garde composers. She won the grand prize in the Bonn Beethoven Festival competition in 1977. In the years to come, Albert Hirsh, chairman of the piano department of the University of Houston often remarked that the accordion students had raised the standards of the entire music program at the university. For this spectacular success, Bill Hughes should receive a great share of the credit. Bill and I organized The Concert Trio in 1949, with the late Len Manno, who was contrabassist with the Houston Symphony Orchestra. With two accordions and a string bass, we rehearsed faithfully for at least four hours daily, five days a week. We maintained this schedule for more than 10 years. Our concert debut was made with the Houston Summer Symphony in 1950, when we played Vivaldi's Concerto in D Minor, and one of Handel's organ concerti. We also presented a full concert that year at the Music Hall in Houston. We were employed for a time as a substitute for the pit orchestra by the Four Arts Theatre. Music was composed for us by Arthur Hall for the presentation of a modernized version of Shakespeare's Twelfth Night, and by William Rice for Shaw's Androcles and the Lion. Rice's music from Androcles was later rearranged for full symphony orchestra and presented by the Houston Symphony in their regular subscription concerts. Imagine the pleasure we had in seeing in the program notes that a symphony orchestra was playing a transcription of a work originally composed for the accordion! Eventually we had the opportunity to audition with a new conductor of the Houston Symphony, Efrem Kurtz, who was so impressed that he immediately telephoned his agent, Kurt Weinhold of Columbia Artist Management and arranged an audition. We drove to New York non-stop and arrived so exhausted that we had no energy left to be nervous. We played many things for Weinhol, but he liked our Bach the best, and fortunately we knew about 45 minutes of Bach's music at that time. After that we played many concerts, booked by Columbia Concerts, Community Concerts, the Civic Concert Association, Cooperative Concerts, Inc. and the Municipal Concert Association. A recording for Capri Records brought more engagements and the fan mail came in droves from Russia, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Ethiopia, Japan, France, Germany -- everywhere. Bill Hughes and I received an award from the American Accordionists' Association in 1957 for having played 110 concerts in one season. After the Trio disbanded, Bill and I continued to concertize as the Palmer-Hughes Duo. In 1963 we received the Award of Achievement from the American Guild of Music. For our concert work, we first used accordions with 160 basses, in order to increase the range of single notes available for the left hand. This was the period when free base development was in its infancy and Bill Hughes made several important suggestions which were incorporated in construction of early models. When the stradella free bass instruments were fully developed, we returned to using 120-bass accordions. In our performances we played these combined stradella and free bass instruments, utilizing both features about equally. Here it may be well to comment, since this is the point that Bill often made, that the university faculty was never critical of the standard stradella system, and a great amount of the required literature was, in fact, performed on standard stradella instruments. Free bass systems were welcomed for the extended range they afforded, but were not required for enrolling accordion majors. Along with our concert activities, which included a tour of Italy in 1967, with appearances in Castelfidardo, the home of the accordion, and in San Marino, Bill Hughes and I conducted numerous five-day seminars throughout the United States and Canada. These busy activities are a only a small part of the story of Bill Hughes. From 1946 to 1967, he maintained a very full schedule of teaching private and class lessons. He was in great demand as an entertainer, and especially as a jazz musician. In the jazz field he was outstanding among accordionists, and he played with large orchestras, including those of Henry King, Ed Gerlach, Buddy Brock, and others, not to mention numerous smaller groups. In the midst of this extraordinary schedule, the Palmer-Hughes Accordion Course was being written. The first book, released in 1952, met with tremendous success. From everywhere came the continuing cry for more books. By 1961 there were 10 books in the course itself, each advancing to a higher level of difficulty.  Bill

Hughes contributed not only many hours of work to the writing of this

course, but a great share of teaching ideas and concepts, skillful but

easily playable arrangements, and constant suggestions for improvements,

which our publisher was kind enough and farsighted enough to accept and

execute. The work of Bill Hughes was in no small way responsible for the

phenomenal success of this widely-acclaimed series, which, to date, has

sold a total in excess of eight million books. These books are still selling

over 250,000 units annually, and presently sales are on the increase again. Bill

Hughes contributed not only many hours of work to the writing of this

course, but a great share of teaching ideas and concepts, skillful but

easily playable arrangements, and constant suggestions for improvements,

which our publisher was kind enough and farsighted enough to accept and

execute. The work of Bill Hughes was in no small way responsible for the

phenomenal success of this widely-acclaimed series, which, to date, has

sold a total in excess of eight million books. These books are still selling

over 250,000 units annually, and presently sales are on the increase again.Bill Hughes was also one of the organizers of the Houston Accordion Symphony which began, to the best of my recollection, around 1954. The members soon voted that the name of the organization be changed to the Palmer-Hughes Accordion Symphony. The standards of this group were extremely high.  The

president of the organization, Anthony Zinnante, appointed an audition

board, and new members were accepted only when they met the rigid standards

of the board. All members were frequently re-examined. The group labored

to build a vast repertoire of orchestral concert material. Bill Hughes

wrote hundreds of arrangements for the symphony and directed them in concerts

at the Palmer House in Chicago, Carnegie Hall in New York City, the Presidential

Arms in Washington, D.C. and in many other cities. The

president of the organization, Anthony Zinnante, appointed an audition

board, and new members were accepted only when they met the rigid standards

of the board. All members were frequently re-examined. The group labored

to build a vast repertoire of orchestral concert material. Bill Hughes

wrote hundreds of arrangements for the symphony and directed them in concerts

at the Palmer House in Chicago, Carnegie Hall in New York City, the Presidential

Arms in Washington, D.C. and in many other cities.In his latter years, Bill continued to teach private lessons at his home in Collegedale, Tennessee. Bill is survived by his wife, Mary, three grown children, William III, Patricia and Michael, and two step-children, Randall and Kevin. He was a very active member of his church and played accordion at the weekly services and for many church-sponsored occasions. He was an humanitarian, and for the last four years of his life he performed every Sunday for the inmates of the Hamilton County Prison near Chattanooga, Tennessee. He volunteered his services at the local schools to assist members of the high school band who wished to make more rapid progress. He was highly respected and loved by his community, as all of us who knew him can well imagine. When he became too ill to leave his home, the choir from his church serenaded him under his window. On the day Bill Hughes died, August 25, 1978, the flag on the high school campus at Collegedale was flown at half-mast.

From Accord Magazine, USA. Reprinted courtesy of owner/editor Faithe Deffner. Back copies available. |

|

© Copyright 1999 Accordions Worldwide. All rights reserved. |

Dr.

Willard A. Palmer, who wrote this article, is fondly known as Bill Palmer

in accordion circles. His accordion career may be divided into three

segments -- performer, composer, and educator. In each area, he has

distinguished himself sufficiently so that other men might call it a

full, successful career in itself.

Dr.

Willard A. Palmer, who wrote this article, is fondly known as Bill Palmer

in accordion circles. His accordion career may be divided into three

segments -- performer, composer, and educator. In each area, he has

distinguished himself sufficiently so that other men might call it a

full, successful career in itself.