|

|

|

|

1935

to 1995

|

|

Thanks

to Prof. Friedrich Lips

for writing this memorial to his great friend Mogens Ellegaard. Thanks

also to Dr Herbert

Scheibenreif for translation to English and German languages.

|

My

memory flicks through sides of biographies, which are dedicated to the

contact with human beings dear to me - composers, performers, and somehow

I am surprised by the fact that some of them emerge in my memory particularly

often. These memories warm the soul. I would like to express some special

thanks, but, unfortunately, it is already a bit late... My

memory flicks through sides of biographies, which are dedicated to the

contact with human beings dear to me - composers, performers, and somehow

I am surprised by the fact that some of them emerge in my memory particularly

often. These memories warm the soul. I would like to express some special

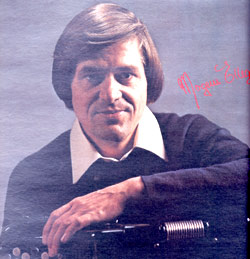

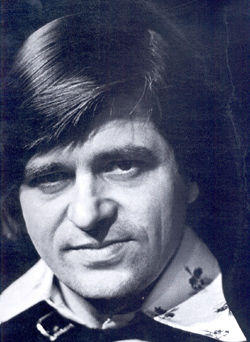

thanks, but, unfortunately, it is already a bit late...I got to know Mogens Ellegaard in Klingenthal in 1975, although we had already heard from each other - we both had recordings from each other. He had come with his own students in order to listen to the competition and to meet, at the same time, with his future wife, the accordionist Marta Bene from Hungary. This was a complicated love story, but after all, they had a lucky, but not very long common life. As first prize-winner of 1969, I was invited by the organizers of the international competition in Klingenthal to perform in the evening concerts. I still remember the sincere joy in the face of Ellegaard, at the moment I first became acquainted with him. During lunch, we sat next to each other and talked in German. Suddenly the waiter brought us both, unexpectedly for me, a large jug of beer. He explained that my new friend had made this order, whose payment he naturally took over unnoticed by me. Mogens repelled my attempts to pay with a smile: "The money is round!". During the gala concert, at which the Warsaw Accordion Quintet under the direction of Lech Puchnovski, Vladimir Besfamilnov and other musicians took part, I played the Sonate No. 3 by Vladislav Zolotariev. After this concert I won many admirers and new friends, among others Elsbeth Moser. Mogens with Marta and Elsbeth expressed the desire to spend the evening together and we drove to my hotel in Plauen, 30 kilometers from Klingenthal. We celebrated till dawn. It was an unusual night with new friends. They were perfectly delighted by Zolotariev's music and expressed even words of sincere sympathy for me. One must say that after this appearance my international career began. Lech Puchnovski invited me to Bialystok (Poland) for his annual summer courses, Fernand Lacroix to the annual seminars in Châtel (France), and after some years Ellegaard organized two concert tours for me in Scandinavia, and Moser in Germany. That evening Mogens expressed the enormous desire to purchase a bayan "Jupiter" like I had. The next morning, I would have arrived almost too late at the airport Berlin/Schönefeld, for the return flight to Moscow, where a telegram already awaited me, with the message that Vladislav Zolatariev was no longer alive ...  The

following year I met Mogens and his young wife Marta at the annual summer

seminar in Châtel (France), which was organized by Fernand Lacroix.

Besides the concerts and master classes, we spent much time together.

I was pleased by his way of teaching - with the instrument in his hands,

the convincing reasons for his own demands, an abundance of interesting

associations, always with his own, special humor. The

following year I met Mogens and his young wife Marta at the annual summer

seminar in Châtel (France), which was organized by Fernand Lacroix.

Besides the concerts and master classes, we spent much time together.

I was pleased by his way of teaching - with the instrument in his hands,

the convincing reasons for his own demands, an abundance of interesting

associations, always with his own, special humor. Again we spent the night before leaving France together until the morning, with exquisite beverages, full of discussions about problems of the bayan. When leaving he said to Marta: "We must reserve one night for Friedrich each year!" (literally: "pull out one night from the calendar"). The message that the most prominent musician in the west expressed the desire to purchase a bayan "Jupiter" evoked a certain euphoria of the management and the masters of the Moscovites bayan factory, in the factory's everyday life. Finally, it was an acknowledgment of the Russian way of thinking, of how to construct instruments. A. Ginzburg, director of the bayan factory, vehemently supported the idea of constructing bayans "Jupiter" for export, even more, as one of the most important musicians in the west was concerned, and he asked his best masters to do this job: main technical designer J. Volkovitch and V. Vasiljev, who was prominent with the manufacturing of the reeds. Mogens, as did most bayanists and accordionists in the west, played on a 9 row-instrument, 3 rows of melody (free bass) arranged near the bellows, and 6 rows of standard bass further from the bellow. In Germany I told him that nobody makes 9 rows in Russia, but only 6 rows with the converter key on the left keyboard. Then he asked rather timidly: "O.k., the future will belong to the 6 row-instrument with converter, I will try to study it, however, please do make a C-griff (C system) bayan for me with the low notes on the top of the melody bass manual, particularly since I do not have so many years left, in order to be able to acquire my whole own repertoire on your B system, with the basses down". Volkovitch did not have any special problems to build a bayan with the new system for the first time. The instrument turned out to be simply super! Ellegaard was very content with his new bayan and generously thanked all masters. Just as a joke, I later said not once only, that today, nearly the whole world would play on our system. If I would have told anybody at that time that it was impossible in Russia to construct a C-Griff bayan because Mogens who wanted very passionately to purchase a "Jupiter" would probably have begun to study the B-system... This is a joke of course, but Ellegaard's influence on the whole art of playing the bayan was so big in the west that soon all producers in Italy and Germany changed to six-row bayans with converter in the left keyboard. Talking about Ellegaard's personality, one must think of everything he has achieved in life. I think the fact that his being talented artist, the divine grace of the paedagogue and the organizer in international fields permitted to him to succeed in all walks of life, thus leaving an outstanding trace in the world-wide bayan culture. The opening of accordion classes at the Danish Royal Conservatoire in Copenhagen, at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, at the Conservatoire in Oslo as well as the University for Music and Theatre in Graz (Austria) is connected with the name of Ellegaard. Among his pupils there are Matti Rantanen, Owen Murray, Jon Faukstad, Geir Draugsvoll, James Grabb and many, many others.  Ellegaard

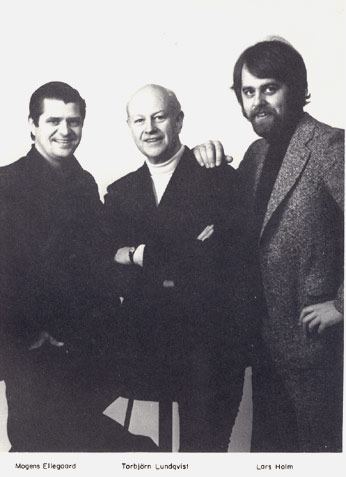

was one of the first to recognize the necessity to create an original

repertoire for our instrument. He worked hard with composers and also

included all new names into this process. O. Schmidt, P. Nørgård,

A. Nordheim, T. Lundquist, N.V. Bentzon, L. Kayser, P. Olsen and many

others, in fact, all Scandinavian composers dedicated their works to him. Ellegaard

was one of the first to recognize the necessity to create an original

repertoire for our instrument. He worked hard with composers and also

included all new names into this process. O. Schmidt, P. Nørgård,

A. Nordheim, T. Lundquist, N.V. Bentzon, L. Kayser, P. Olsen and many

others, in fact, all Scandinavian composers dedicated their works to him.

Ellegaard has arranged an impressive list of the works of Scandinavian composers with indication of the years of their premiere. It is a fact that most of the works from this list are used constantly by accordionists of almost all countries in their educational and concert repertoires. Ellegaard's co-operation with composers is a valuable contribution for the world-wide "treasure-chest" of bayanists. Ellegaard was driven by unbelievable discipline in his life. His day started at 5 o'clock in the morning. He practiced on the instrument, answered letters and then drove to work at the conservatoire at 9 o'clock. In general, he was an unusually well educated human being. He had excellent knowledge of English, German, French, Norwegian, Swedish and, of course, Danish. When I got letters from him, and I collected not just a few, as there was no fax or internet at that time, even a telephone call had to be ordered one or two days before, it was always a real pleasure how he developed his thoughts in his letters. First why the letter was written, then a small report on his activities, afterwards he wanted to know things about my family and he told me how he spent his time with his family, and in the end he absolutely let flow the element of humor, the whole letter being written in outstanding German. Contact with him always presented an enormous pleasure to me. Mogens showed himself, and that in relation to the environment, always in a very humorous way. He estimated humor and reacted to the jokes of others both skillfully and in a very open way. I remember when we were sitting in the restaurant together with his class after my concert in the Danish Royal Conservatoire in Copenhagen. One of his students was wearing a red roll neck. He wears it for your honour, because you come from Moscow! - was Ellegaard unable to resist to remark. In general, he was glad to make fun of the political system in the Soviet Union at that time. You neither have democracy nor the right to free expression of opinion! - he continued to put pressure on me the whole evening. But, in the sense of humor, we reacted differently, therefore I called with appropriate pathos: Why not? We also say what we want! Thus, I can go to the main place of Copenhagen and say: the Prime Minister of Denmark Nilsen is an idiot! Can you do the same in Moscow? Certainly! I can go to Red Square in Moscow and also say: the Prime Minister of Denmark Nilsen is an idiot!  We

laughed all evening. Generally Mogens knew excellently how to receive

his guests, as well as to organize tours and master classes. In Mietne

(Poland) in 1992, on his initiative the International Accordion Society

IAS was founded consisting of five board members: Matti Rantanen (Finland),

Lech Puchnovski (Poland), Mogens Ellegaard (Denmark), Joseph Macerollo

(Canada), Friedrich Lips

(Russia). President of the executive committee should be either Puchnovski

or Ellegaard. We

laughed all evening. Generally Mogens knew excellently how to receive

his guests, as well as to organize tours and master classes. In Mietne

(Poland) in 1992, on his initiative the International Accordion Society

IAS was founded consisting of five board members: Matti Rantanen (Finland),

Lech Puchnovski (Poland), Mogens Ellegaard (Denmark), Joseph Macerollo

(Canada), Friedrich Lips

(Russia). President of the executive committee should be either Puchnovski

or Ellegaard. But none of them wanted to take over this responsibility and finally, among five members of the board Ellegaard proved to be "the first among equals". Finally, he was motor and generator of various ideas. Besides, thanks to his knowledge of languages he was able to communicate with each of the four other members of the board. We tried to realize the following ideas: standardisation of all instrument models, standardisation of terms in musical works, independent of country and publishing house. At the congresses in Finland, Germany and twice in Italy we agreed on most questions despite large difficulties. But, unfortunately, all compiled ideas remained on paper, because, after Ellegaard had passed away in 1995, no leader could be found to complete the work. We all were convinced of the importance of a strong personality for the completion of a certain work.  I

remember our last meeting at the accordion festival in Toronto (Canada)

in 1994. As the organizer of the festival Joseph Macerollo succeeded in

bringing together the stars among the accordion artists: Mogens Ellegaards,

Hugo Noth, Matti Rantanen, Mini Dekkers... Joseph Macerollo premiered

R. Murray Schafer's "Accordion Concerto" with symphony orchestra,

I presented new original music of Russian composers for bayan. I

remember our last meeting at the accordion festival in Toronto (Canada)

in 1994. As the organizer of the festival Joseph Macerollo succeeded in

bringing together the stars among the accordion artists: Mogens Ellegaards,

Hugo Noth, Matti Rantanen, Mini Dekkers... Joseph Macerollo premiered

R. Murray Schafer's "Accordion Concerto" with symphony orchestra,

I presented new original music of Russian composers for bayan.Coincidentally Ellegaard and I had booked the same return flight to Frankfurt. We sat in a row next to each other and, the whole night, we talked. It was a further completely mad night with an unusually interesting interlocutor, with a personality! Everything began with an aperitif before dinner. I ordered a small bottle of whisky "Johnny Walker", and Mogens a bottle of "Martell". I was surprised: Mogens was a big admirer of whisky and I had got accustomed to this noble beverage, when he brought me a one litre bottle "Ballantine" as a gift on his first trip to Moscow. But after a few minutes everything was as usual again: "Why did I order this Cognac? I should have ordered whisky like you!" - and as the hostess came by next time, he ordered whisky for me and himself. Without closing an eye, we sketched different projects for the development of the art of bayan on international level. We spoke about the fact that one should help the young people to find work and arrange concert tours; on the initiative of our international society we planned the founding of a new international competition as well as the organization of small tours for young winners as an award instead of prize money. Generally Ellegaard did not appreciate competitions, particularly the "Coupe Mondiale" which he did not consider serious enough. We continued our discussion about the standardisation of the instruments and terms in the world-wide bayan literature, only interrupted by the conversations with the hostesses concerning the beverages. We continued to order whisky regularly ... Suddenly it occurred to Mogens: She has not come for a long time! - and he pressed the button, in order to call the hostess. Probably they will not given us anything more. We already have drunk quite a lot, - I expressed my fear carefully. Surely we will get some more, certainly! Naturally they brought us bottles. In addition Mogens personally went to the hostesses and brought back some whisky. That was him!. If he had an aim, he aways reached for it. All in all everyone of us, as far as I remember, had drunk seven bottles (about 350 milliliters). Sometimes I had the impression that he was missing the contact to colleagues. And actually, he had the enormous house with his wife in Sweden, in a large forest, there was nobody else; very seldom contact with his students in Denmark, no discussions on university level, with nobody... While working in the jury of competitions in Witten, Moscow or in the meetings of our international society I felt, how he longed for discussions with colleagues. Now Mogens would be 70 years old. But unfortunately it has been already 10 years that he is no longer with us. Were his pupils, as the following generation, grateful, and we? He has set himself a monument dedicated by literature, the photographs as well as by his various activities. But I think, it would have been necessary to create a "Mogens Ellegaard-Prize" as regular competition for young musicians. It took place in Copenhagen once, it was planned to be annually in different countries of Scandinavia. However, it could not be realized. It would also be interesting to collect articles about this outstanding musician; notes about Ellegaard's educational principles could be taken by his pupils or from the memories of colleagues and friends... One could still invent much! We should learn to be grateful to God not only for our own appearance in this world... |

|

March 2005 is the tenth anniversary of the untimely death from leukaemia

of Mogens Ellegaard, which is an appropriate time to look back on his

career and achievement. In the spring of 1995 he was due to play a major

role in an international accordion festival in Amsterdam in which many

international stars were taking part. His death on 28th March, just

two weeks before the festival, turned several of the recitals into memorial

concerts in his honour. His loss at just 60 years of age hung heavily

over the event as the organisers dedicated it to his memory. |

Mogens Ellegaard: A 75th Anniversary Tribute |

The lecture and concert at the Royal Academy of Music on 25th November 2010 celebrating the 75th Anniversary of the birth of the late Mogens Ellegaard was a most moving occasion. In his opening address Owen Murray declared that without Ellegaard’s pioneering work neither he nor the students would be here and the same would be true for students and teachers in a number of other conservatoires across Europe. ‘Mogens untimely death at 60 years was a devastating blow to his family, friends and accordionists worldwide’ Owen spent eight years in Denmark between 1974 and 1982 studying music under Ellegaard at the Royal Academy of Music in Copenhagen. Owen’s talk was illustrated with personal stories and CD recordings as well as Ellegaard himself talking in a BBC broadcast, and with notes and music scores projected for the audience on a screen. Owen reminded the audience of Ellegaard’s frequently told story of how he began playing the accordion at the age of eight after an accident had hospitalised him. ‘He fell off a balcony. Fortunately for him, his parents and future generations of accordionists, it was close to the ground. His parents gave him an accordion to cheer him up’.As a young boy he began to practice and play the repertoire of Toralf Tollefsen. In an open letter to Tollefsen published in Norway to celebrate his 80th birthday in 1994 (one year before Mogen’s own death) he revealed how ‘in 1954 I…..decided to embark on a career as an accordionist and model myself as a ‘mini Tollefsen’. Ellegaard copied Tollefsen’s repertoire and played it on an extended visit to the USA between 1955 and 1957. He particularly liked The Marriage of Figaro Overture as played by Tollefsen, which Owen played from a CD followed by Ellegaard’s own performance of The Flight of the Bumble Bee. Ellegaard’s early recordings were all of popular classics and entertainment music, many of them à la Tollefsen. Returning to Denmark in 1957, Mogens played a light music concerto composed for him by a pianist/composer Vilfrid Kjaer (1906-1969). In the audience on that occasion was the composer Olé Schmidt. He expressed admiration for Ellegaard’s skill as a performer and the great possibilities of the free-bass accordion, but was very critical of the music itself. Ellegaard asked if he would write a concerto. Schmidt agreed immediately and in 1958 the premiere of Olé Schmidt’s ‘Symphonic Fantasy and Allegro’ op.20, took place in Copenhagen. This concerto has a special place in accordion history and was the catalyst in a whole new Scandinavian repertoire for the free-bass accordion, later called accordeon. Following a CD extract of the first movement Owen argued that this work marked a turning point in Ellegaard’s career. He not only played it on many occasions throughout the world but he resolved to persuade as many composers as he could to write original works for him. He was in this endeavour extraordinarily successful. Between 1960 and his death in 1995 he had persuaded Scandinavian composers to produce over 100 works for him. He worked incredibly hard, always playing what had been written, arguing that whether the work turned out to be good or otherwise, it should be performed because composing and performance was the process by which we learned to produce new and better music for what was essentially a very young instrument. Ellegaard was an incredibly disciplined person with great energy and commitment. If Owen had a lesson at 9.00 am and came to warm up at 8.00 am, he would find Mogens already practising in his room. Owen illustrated Ellegaard’s mastery with a CD recording of Olé Schmidt’s Toccata No1, a demanding work that continues to be one which stretches the abilities of the most able students. In 1970 he was invited to form an Accordion Department at the Royal Danish Academy of Music in Copenhagen which marked a further milestone in his career. It was a landmark occasion in accordion history. Creating educational possibilities for young accordionists to study at conservatory level meant a great deal to him. “When I started, there was absolutely no accordion culture unless you define accordion culture as ‘oom-pah-pah, or the Cuckoo Waltz – that sort of thing. The free-bass accordion didn’t exist, it was entirely unknown when I was a child. At that time the accordion world was living in splendid isolation. No contact at all with the outside musical world. Concerts for us consisted of Frosini, Deiro repertoire or folkloristic music. The possibilities of getting a formal education on accordion were nil. The accordion was not accepted at any of the higher music institutions. The possibilities for a soloist, for the best players, would be variety ‘night club ‘work, Saturday night shows. This is what I was doing when I was very young”. In 1977 he was promoted to full professor. In the latter part of his career Ellegaard encouraged his students to concentrate on the ‘new literature’ and move away from transcriptions which he argued had been a ‘temporary solution’ to the lack of original works which were needed to give the accordion an identity of its own in serious music. In 1975 Ellegaard met Friedrich Lips who invited him to Moscow. With Lips’ encouragement the Jupiter Accordion Factory were persuaded to produce a ‘C system’ bayan for Ellegaard - the first they had ever made. It led to the spread of the modern ‘convertor’ instrument and the replacement of the ‘9 row’ system. Later Ellegaard persuaded the firm of Pigini in Italy to produce a range of convertor instruments suitable and small enough for young students, and professional concert models. This collaboration was another fundamental development affecting both teaching and the manufacture of instruments. Ellegaard was very proud of his Pigini Sirius Bayan and later his Mythos, arguably the finest accordions ever made. Today Pigini accordions are played by students and top professional players all over the world. Ellegaard’s effect on teaching, manufacture and repertoire of the modern accordion was not without controversy but it was profound, which will ensure that it will never be lost in the shadow of history. Owen concluded his address with a discussion of the performance of Arne Nordheim’s Concerto ‘Spur’. This work later recorded in the U.K. was premièred in Oslo University with the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra. The première was attended by Toralf Tollefsen. Mogens afterwards wrote of this in his open letter to Tollefsen: Arm in arm with your old teacher Otto Akre you came to congratulate me after the concert and that gesture was for me more precious than the personal satisfaction I had of being the soloist with the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra…..Your words of encouragement on that wonderful evening were so positive on the new music and my performance that it greatly encouraged me in my chosen path… Following these words Owen played Ellegaard’s recorded performance of ‘Spur’ with the score on the screen and concluded his address. Owen’s students then performed a concert of a number of works written for Ellegaard that included Ole Schmidt, Toccata No2 (1964), Arne Nordheim Flashing (1966), Poul Rovsing Olsen, How to Play in D major Without Caring About it (1967), Vagn Holmboe, Sonata No1 (1979), Bent Lorentzen, Tears (1992). In the moving Introduction to the concert Owen wrote: ‘….we carry on his work today. Thank you, Mogens. You were an inspiration’ The students splendidly demonstrated the force of his words. |

|

Site constructed and hosted by: Accordions Worldwide at www.accordions.com

© Copyright 2005 Accordions Worldwide. All rights reserved. |