You have been performing regularly in major music festivals. Can you tell us about these experiences? You have been performing regularly in major music festivals. Can you tell us about these experiences?

|

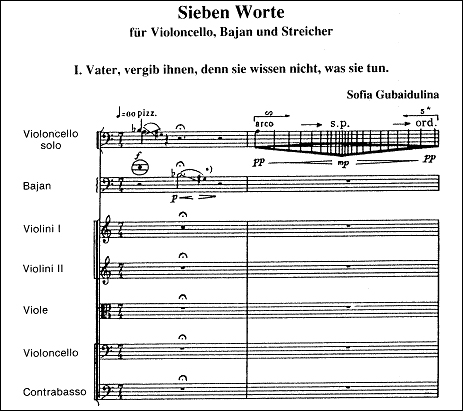

There are many memories, and there is one which really sticks out. Once I had the privilege to play Seven Words by Sofia Gubaidulina with Arto Noras, who is one of the biggest name cellists on this planet. He just turned 70 last year. There are many memories, and there is one which really sticks out. Once I had the privilege to play Seven Words by Sofia Gubaidulina with Arto Noras, who is one of the biggest name cellists on this planet. He just turned 70 last year.

This Maestro spent a long time with the very beginning of the piece during our first rehearsal together. His requirements for the quality of what I should do were relentless. 'Can’t you do it better?' 'Can’t you do it better? He kept pushing 'can’t you do it with this kind of sonority and this quality?" and all the time, I was sweating it out.

Because this musician is one that I truly respect, I kept really trying to do my best, and finally after quite a while I said to Maestro Noras "I have tried everything and this is really the best I can do" and he looked over at me and said "ok", and then we went through the rest of the piece in 15 minutes, and he was really satisfied.

I understand what he wanted to say, and later on I heard from some other Cellists that it's quite normal for him to 'test' new chamber music partners on a quality basis seeing if they can do it better, and this to me was a very profound experience because, normally I pass this passage in my own practice very quickly. So it gave me a clearer picture of these quality artists and what they strive for. Apparently I managed, because I have since been invited back to Noras’s festival five times. I understand what he wanted to say, and later on I heard from some other Cellists that it's quite normal for him to 'test' new chamber music partners on a quality basis seeing if they can do it better, and this to me was a very profound experience because, normally I pass this passage in my own practice very quickly. So it gave me a clearer picture of these quality artists and what they strive for. Apparently I managed, because I have since been invited back to Noras’s festival five times.

So, there are many such moments and rather many experiences. Of course, some of the best experiences have been when famous artists have come to me to see if I would play with them, or being re-invited to perform with Symphony Orchestras, and to be welcomed back with them. Even though I’m not so old, I’ve performed quite a lot, so there are many such experiences.

In the general musical society, I have never had a negative experience. Sometimes of course, I have disagreed with some artists about things like interpretation, or sometimes the chemistry didn’t function as well as it could have, but all things considered, it's 95% positive, and I have never been rejected on the basis that I am an accordionist.

However, I have had to prove to them each and every time that I can do the job. It’s hard world out there. Sometimes I think that the young accordionists don’t realize how hard it is. It can finish people. There are possibilities to perform with Orchestras, or to perform with extraordinary artists, but it is just a possibility, and the important thing is what we do with this opportunity, and if you can manage.

|

We once talked about talented accordionists and their lack of drive to continue to study and develop, after their competition successes. What has motivated you to continue your drive for excellence and do you have general advice for young accordionists looking towards managing their education and studies? We once talked about talented accordionists and their lack of drive to continue to study and develop, after their competition successes. What has motivated you to continue your drive for excellence and do you have general advice for young accordionists looking towards managing their education and studies?

|

I just met Joe Macerollo who was in the Sibelius Academy to conduct a seminar and I had dinner with him. He is a wonderful and highly educated person. When I spoke with him, I realised that this individual has contact to the ‘music world’. For example, he was ‘fluent’ in talking about Glenn Gould, because he knew best friends of Glenn Gould. I started to think to myself 'why' I respect some people. Geir Draugsvoll is Professor of accordion in Copenhagen, where he is doing great, but he too has always had these contacts to the music society, mixing with people even more talented than we are. Angel Luis Castaño the same, Stefan Hussong the same, Teodoro Anzellotti the same, and probably the key to this survival and continued working is the greater perspective.

A competition perspective is just a a really tiny, a micro-cosmos of all musical aspects. One needs to face the academic world early on in music, and understand that the word 'academic' is not a bad word. The Juilliard School of Music is an Academic Institution, the Tchaikovsky Conservatory, the Paris Conservatory, these are Academic Institutions just like the Sibelius Academy. There you meet people who are committed. A competition perspective is just a a really tiny, a micro-cosmos of all musical aspects. One needs to face the academic world early on in music, and understand that the word 'academic' is not a bad word. The Juilliard School of Music is an Academic Institution, the Tchaikovsky Conservatory, the Paris Conservatory, these are Academic Institutions just like the Sibelius Academy. There you meet people who are committed.

There are pianists who don’t finish their career by winning the Chopin competition, they ‘begin’ their careers from that. There are conductors who won competitions, but their aim is far longer, their aim is really a minimum of 20 years, the time when they collect their repertoire,when they increase their expressional and technical capacity, and when they learn necessary social skills.

And, this is where I come to so called ‘Academic’ education. To be without it, one cannot survive long term. It gives you the ideals. For example, there are composers, and there are composers. There are composers who decided that they will be composers without any formal education. It's like an Architect who didn’t have any formal education as an Architect, someone who just decided to be an Architect. One can not learn anything from him.

Then there are those people who have really studied profoundly from Palestrina to music of our times, and then started to compose. They are smart. They are talented. From such people, one can get the motivation to go on. They all realise that themselves, or great instrumentalists would never consider themselves to be ready by the age of 40. They aim always much longer, and I would say something like this is the key.

If one thinks short term, one is satisfied very quickly. One gets what one wanted, but nothing more. I still consider myself as a music student, and probably this is what keeps alive, my interest to play. Every practice session is not to repeat something that is already done, but to learn something that I can’t do. I know this is the same with my colleagues who play piano and violin. They try to improve and reach their own personal ideals.

In accordion we don’t have as many, or such inspiring role models as pianists or cellists have, such as Yo-Yo Ma or Pablo Pascals, so in fact, we are actually creating this heritage now.

In accordion for example, Mogens Ellegaard was an incredibly big name, and I think people don’t understand how big a musician he was. Sometimes I think his name is forgotten in some countries, but this is just one person, and we are still lacking this overall ‘role model’ thing. For pianists its easier. Sviatoslav Richter and Vladimir Horowitz were there, so even though the young pianists could play the Chopin Etudes very fast, they know that they are not yet Horowitz, and they are not yet Richter, so they have to continue aiming high and they have to continue aiming long. We as accordionists are short term, at the moment. However, I would say that even this will change in the next 50 years. What would be the world without ‘role models’? It would be nothing.

Mika is pictured above in a photo by Heikki Tuuli.

|

You are still teaching at the Sibelius Academy. In addition, you also present Master Classes in various countries around the world. How big a part of your career is your teaching work at the moment? You are still teaching at the Sibelius Academy. In addition, you also present Master Classes in various countries around the world. How big a part of your career is your teaching work at the moment?

|

Actually, two years ago, I stopped teaching Master Classes, and there will never be another one. But, ‘Seminars’ will still take place. First of all, it took me some years to understand in a Master Class, who is the ‘Master’, the student or the teacher, and what does this mean? Then I got a bit frustrated, because teaching is actually quite long term work. Actually, two years ago, I stopped teaching Master Classes, and there will never be another one. But, ‘Seminars’ will still take place. First of all, it took me some years to understand in a Master Class, who is the ‘Master’, the student or the teacher, and what does this mean? Then I got a bit frustrated, because teaching is actually quite long term work.

I Googled myself, and I was surprised to learn that I had many more students than I knew of, because there are people who included me as their 'teacher' based on a few days meeting. So two years ago, I decided not to conduct any more Master Classes again. If someone asked me to teach a Seminar, that’s fine. However, I will also no longer teach Seminars in any private music/accordion schools. I will only visit in official Institutions, because I think that this at least guarantees that the students have some knowledge. I have also faced situations where the students should be studying under my students, and not under me!

So I became a bit strict on this subject. The last Seminar I did, was at the Paris Conservatory in March.

Pictured right: Mika outside the Ikaalinen Church, Finland in 2012. Photo by Minna Plihtari.

Teaching it is quite a big part of my life. More or less, I dedicate myself to my class at the Sibelius Academy. I think teaching is a long process. If one takes in a 19 or 20 year old person as a student, and then considering at the Academy we have about 5 - 5 1/2 years of study time to produce a developed musician, it's a hectic five years. Normally you have fix many technical aspects and psychological aspects, and the students should learn many things about performing traditions and about repertoire etc.., so there is a lot to fit in.

I take it quite seriously, but it is happy work I must say. The responsibility is pretty heavy, because when they graduate by the time they are 25 or so, I have to send them out to the world, and they are not ready. I was not ready! Then you observe what happens. I take it quite seriously, but it is happy work I must say. The responsibility is pretty heavy, because when they graduate by the time they are 25 or so, I have to send them out to the world, and they are not ready. I was not ready! Then you observe what happens.

As I was saying, just today in fact to one student, that I don't actually care so much how they play the Bach or not, but what I really care about is what they learn through playing this Bach. Bach cannot be polished at the very moment, but it's learning about the principles of playing, the history of the culture and style, things that will appear during the coming years. You are not only practicing the piece, you are practicing the things to come. I just touch the surface.

It is known that Sight Reading is a very important part of music. Sviatoslav Richter was playing as a rehearsal accompanist at the Odessa Opera, playing for Operas and Ballets. Nothing was polished, but this individual got an important part of his music education by touching the surface of this music, which he used later on, to create wonderful things.

I don't want to polish everything, but I would like to see my students when they are 30 or 35, to see how the seed has grown. I think something is wrong in music education, at least in accordion, if a person for example, plays a Scarlatti Sonata for 1-2 years and only thinks of the moment, or for the competition. Teaching has to be targeted to the future, as this creates the situation that the person finally has the tools to play well.

The technical biological brain doesn't develop in a few years. For example, my trills are now better than they used to be 10 years ago. My 'biology' needs the years to learn it and the brain needs the years to control it and to have the right tools to sophisticate this process takes time, so teaching is very responsible work.

Sometimes a student doesn't realise what I'm trying to give them, and I definitely don't want to produce competition winners etc.. I think over a much longer distance. When one of the competition winners is gone, some of the students who were not completely polished at the time will survive longer. There is a person who got a very low placing in the Chopin competition in Piano, but after years, that individual has become one of most important Chopin interpreters on the planet. Richter didn't win all the competitions he took part in, but he became a monumental figure in the history of music.

It takes a lot of energy to be a teacher, and I don't see the result, until, I would say, a minimum of five years after the graduation. This is when I see what is happening, rather than getting prizes in competitions when they are 22 or 23.

I know what it means to play year after year after year, in these big things, so I guess I know first hand what qualities one needs.

|

As you work with students in various teaching situations, do you come across a common theme of what you find to work on? As you work with students in various teaching situations, do you come across a common theme of what you find to work on?

|

Well I do. I have yet to meet a student who's technical command is perfect. So, neither is mine, but let's say it's a bit more developed. Even with these so called 'robotic digital' players, there are things that can be, if not corrected, shall we say, at least sophisticated, and to be really polished. I consider playing an instrument along the lines of this old sentence that 'polishing your technique, is polishing your interpretation.' Well I do. I have yet to meet a student who's technical command is perfect. So, neither is mine, but let's say it's a bit more developed. Even with these so called 'robotic digital' players, there are things that can be, if not corrected, shall we say, at least sophisticated, and to be really polished. I consider playing an instrument along the lines of this old sentence that 'polishing your technique, is polishing your interpretation.'

These are the same thing. Technique isn't separated from interpretation, technique 'is' interpretation, and the body and mind have to function as one. Very often the mind knows more than what the body can do. Then, the interpretation is not yet optimal. Sometimes the mind is less, than the digital command of the body.

In the beginning we play what I call the 'big technique' which is what we see many times at competitions. The reoccurring themes are speed and power. It's like pianists playing without much care or attention to sonority and quality etc.. It's just to be a 'machine gun'. But there are many aspects in technique which have to be polished, or at least given its 'direction'.

Even to play 'legato' is very complicated because one has to consider what kind of legato and under which context do you want the legato to be, and what kind of attack do you want there to be, this is all important.

However to me it always ends the same in teaching. No body, not even the best of what you consider the best 'digital' or 'fast' players, could satisfy all the aspects. There are always these weak areas. After all, technique is not only about speed, technique is about coordination. It is coordination and timing, and mostly there are tiny problems in timing. You can't imagine a piano seminar where a piano teacher wouldn't speak about technique, and only talk about playing without explaining how it works, and what are the minor nuances and how to change from one finger to another etc.., and so the topic is almost never ending.

|

How are your recording projects coming along, and how do you select the works to be recorded? How are your recording projects coming along, and how do you select the works to be recorded?

|

To me, I'm done when I'm done with my recording, then, to me it's ready. It is my work. I have this need to do these things, and it's just my job. I just have to do these things now, as I have some other things I want to learn. The releasing timetable of these things isn't so important. If it comes after two years, I still don't mind because then, it's done. To me, I'm done when I'm done with my recording, then, to me it's ready. It is my work. I have this need to do these things, and it's just my job. I just have to do these things now, as I have some other things I want to learn. The releasing timetable of these things isn't so important. If it comes after two years, I still don't mind because then, it's done.

Pictured right: Mika during his recording of the Bach Vol. 1 CD at Ylistaro Church in April 2012. Photo by Mika Koivusalo.

Every time a new CD comes out, I don't really pay attention to it anymore. When the Vo1. 1 of Bach came out, I got my copies of it, and I think they stayed in the Post Office Box for a week or so, as I had no interest to pick them up, because I had already done them. I had already checked the Booklet and I had listened to the Master CD and that's how I think about it. When on May 9 the Vol. 2 of Bach was recorded and edited, it is the same, it is done. Of course, I'm never satisfied with these things, so I would rather forget them.

Then later I read a review from a Newspaper or Magazine.

When the Tüür Concerto is recorded, it will probably be the same. I will get the Master after a few months, and then a label will publish it sometime, and then the contemporary music CD will be the same. I decided to accept myself as I am. To me its just about going forward, and not to stay on my sofa and just say "I recorded Bach."

I'm always very happy when I have done a recording, so that I can begin to study the next things the day after. It's not time for fireworks, it's just time to say.. ok its done, and then be free from the project. I learn from the projects. I learn a lot from them, but I still have some things to do, and now I have more scores waiting.

It keeps me healthy because if one does too many things simultaneously, everything will be bad. I have a list of things organised up until 2018 and in my case it has to be done this way. I learn quickly, but I also time things very well. This way I can handle this much repertoire for a year. But if the same amount of pieces would be put together, there wouldn't be any order and there wouldn't be any focus.

|

As you complete your series of current recordings and commissions, what plans are on the horizon? As you complete your series of current recordings and commissions, what plans are on the horizon?

|

I played my first recital in 1985 and so in a couple of years in 2015, it will be '30 years' ago. I'm considering a return to some of my older repertoire that year. I played my first recital in 1985 and so in a couple of years in 2015, it will be '30 years' ago. I'm considering a return to some of my older repertoire that year.

Then, in 2017, I will be 50 and some things are planned for that year, rather an unusual project, but more about that later.

I didn't even realise that the time is flying by so quickly, and step by step some birthdays (anniversaries) begin to appear, and I realise that I'm not 20 anymore.

So, in these 30 years I've done a lot playing, not thousands of concerts but a few hundred. Anyone who has such a career on any instrument 'especially on accordion' should at least be a little proud of such achievement. I am, honestly said. These years has been so difficult, but also SO rewarding.

Mika is pictured right in a photo by Heikki Tuuli.

|

|

|

|